Construction in progress

by Marta Ramos-Yzquierdo.

Text for solo exhibition “Em Obras", Blau projects, São Paulo, Brazil.

“Modern art starts with the renouncement of Historic painting.” (1)

INDEPENDENCE WILL DISAPPEAR. It’s a fact. The painting known as “O grito do Ipiranga” (1888) by Pedro Américo, commissioned by the Brazilian royal family in order to glorify the figure of D. Pedro I and to mold a symbol of Independence from Portugal in 1822 into the imaginary, cannot be seen until 2022. This is the year in which the renovations at the Museu Paulista da Universidade de São Paulo will be completed, whose collection the work is found.

Without proposing a discussion around the political signification of the creation of historical myths, in the work and in the museum itself (all of its collection relates to Independence), its decadence and reopening; the reality is that in the next nine years one of the paintings of reference to popular Brazilian culture will only be available to our sight through reproductions.

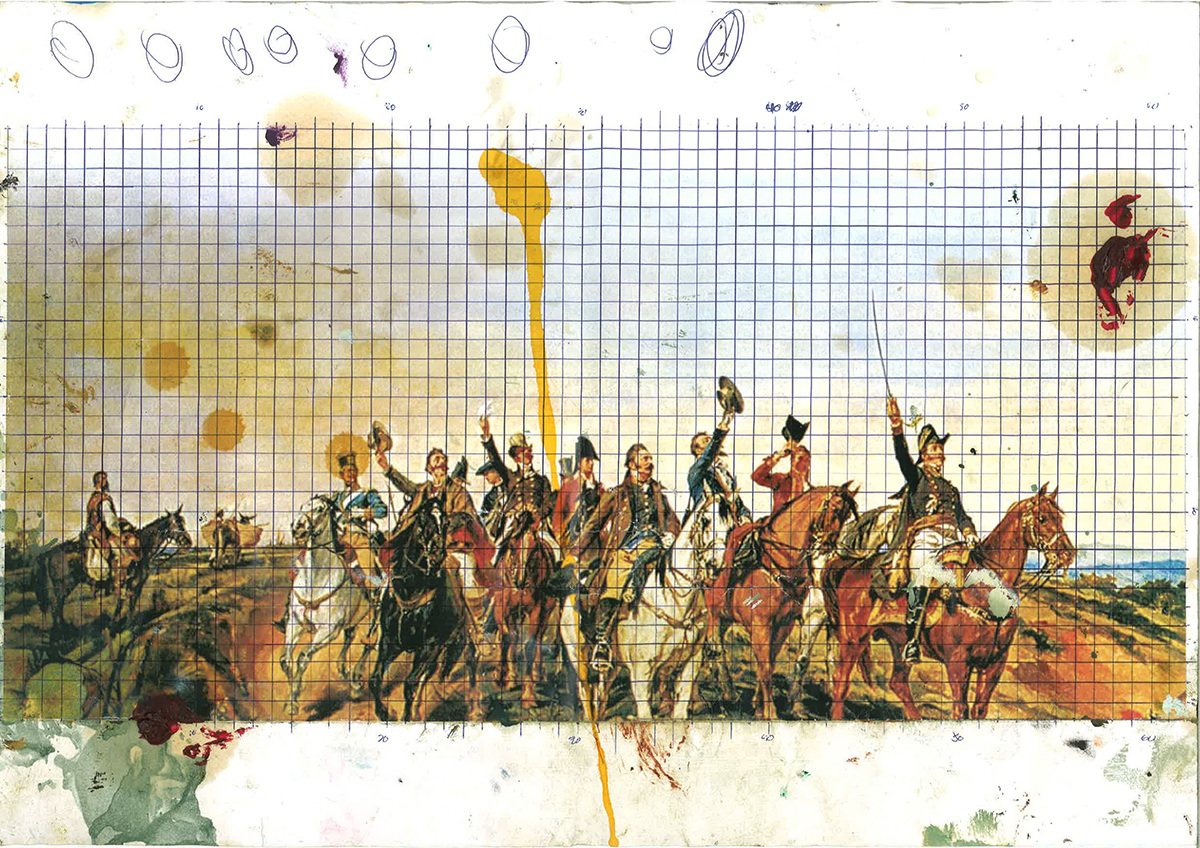

This is the news with which Bruno Moreschi begins to give form to the project “Em obras.” The first proposition is the reproduction of Américo’s famous image through parts and by emphasizing a few details, made by the hands of various “street painters” in the artist’s studio, where he acted as an assistant.

It is the first layer of investigation that the artist has been developing, which in its most abstract form I would call “of the visible and of the invisible.” This is because the original work will become invisible, as its highlights are characters normally unnoticed and uncited in the official history: a drover, a herdsman and a person in the window of a house. They are silent witnesses, the invisible in a visible account.

The reclamation of content also reveals itself in the process: the pieces were produced in collaboration by a team of different painters that commercialized their work by directly negotiating with the client and using the public space as a place of sales. These are the workers or professionals of art, as well as an assistant now and as one during the Renaissance, that remain invisible in the art institution. In this occasion, all of them emerge as artists in the show; they are all authors of the works.

What is interesting in this process are the relations created beyond the concept of artwork or authorship, since we are talking from a space that is part of the validating device of contemporary art. Each of the people hired as a worker to make the copy of an artwork established a relationship of labor. At this point a major question emerges regarding what defines a professional artist, a worker, and therefore, in our contemporary art environment and outside of it.

Dialogue 1:

BM – We’re not going to finish the entire painting, I think its best to show a little bit of the process... What do you think?

P1 - Are you sure?

BM - What’s the problem?

P1- They’re going to think I’m a bad painter.

Skill, dexterity, finishing, process, completion, certainty. A finished product does not leave in sight any part of its process. The work of art is simply a product in a market context, but it has, or should have, a meaning and autonomy beyond this. Contemporary artistic activity does not only fit into the means and systems of production. Besides, its processes are open to criticism and self criticism, to free will or to doubt which may/usually generates stupefaction and/or distaste by a majority of society, even more if its form of materialization – that could take any form – deviates from the traditional fine arts.

Sigmar Polke said that painting was nothing more than a construed moral.

“Independência ou morte,” that is the original title of the Ipiranga work, but INDEPENDENCE IS CIRCUMSTANCIAL for various reasons: because after all we are not talking about what happened along the banks of Ipiranga, but mainly, because, any question that we pose about the relations created in a system depends on its context.

The second action done by Moreschi constituted in the hiring of nine wall painters who could freely choose a color, a shape and a piece of one of the gallery’s wall to apply paint to. The composition was completely determined by them – by chance, they all made rectangles as color proofs, even though in a free layout – without any indication or aesthetic judgment from the artist.

Dialogue 2:

P2 - But I’m a wall painter. I’m used to painting walls...

BM - But it’ll be on the wall.

P2 -? But I always paint in the same way, will I have to create?

BM - You’ll have to choose the way that you find best...

P2 - Anything goes?

BM - Anything.

P2 - So in conclusion I’ll have to create.

The historic materialism divides society into proletariats and capitalists; Hanna Arendt, in Animal laborans, a technician for which the work is an end within itself, and Homo faber, superior producer of thought.

Richard Sennet, on the other hand, proposes a system in which the action of the hand and of the brain act in unison, without denying anyone the ability of this active and reflective pair, and that would reach its maximum potential in horizontal collaborative works (2). Joining Rosalind Krauss (3) ideas, what defines the artistic practice as a series of logical operations performed over cultural terms, to Bourriaurd’s (4), according to whom “making the work is inventing a way of working more than ‘knowing how’ to make such a thing better than other things,” we could think of the installation “Pintores” as a proposition to rethink new social contexts through the reflection of the terms handmade and work relation.

The challenge continues to be the real connection between the world of contemporary art and the society in which it is inserted. What is the concept of work, and the concept perceived over the artist’s work and/or the artist as a worker?

Dialogue 3:

P3 - You can call my wife. Tell her I became an artist. I’m going to finish here and then lay on the hammock.

1. Nicolás Bourriaud, Formes de vide. L´art moderne et l´invention de soi, 1999.

2. Richard Sennet, The Craftsman, 2008

3. Rosalind Krauss, L´Originalité de l´avant-garde et autres mythes modernistes, Paris, 1993.

4. Nicolas Bourriard, op. cit.

* Marta Ramos-Yzquierdo is independent curator.